12 min read

“I learned very early the difference between knowing the name of something and knowing something.” -Richard Feynman

One of my favorite articles on the internet is The Cook and the Chef by Tim Urban.

Tim explains the subtle difference between a cook and a chef:

- A cook follows recipes. He or she reads from a book and follows specific instructions to create a dish.

- A chef invents recipes from scratch. They decide which ingredients to use, where to source them from, and how to combine them in just the right way.

The key difference between a cook and a chef is in the way they think.

A chef thinks from first principles. He or she has to know about nutrition, the biology and chemistry of foods, and the best techniques to use to combine different foods.

This idea of thinking from first principles was popularized by Elon Musk, who once said:

“I think generally people’s thinking process is too bound by convention or analogy to prior experiences. It’s rare that people try to think of something on a first principles basis.

They’ll say, “We’ll do that because it’s always been done that way.” Or they’ll not do it because “Well, nobody’s ever done that, so it must not be good.”

But that’s just a ridiculous way to think. You have to build up the reasoning from the ground up—“from the first principles” is the phrase that’s used in physics.

You look at the fundamentals and construct your reasoning from that, and then you see if you have a conclusion that works or doesn’t work, and it may or may not be different from what people have done in the past.”

Conversely, a cook doesn’t think from first principles. He or she doesn’t need any deep knowledge of nutrition, biology, chemistry, or techniques in order to create the exact same dish as the chef. He or she merely has to follow the recipe created by the chef.

The obvious benefit of thinking like a cook is that you can create the exact same dish as the chef without taking the time to build the recipe from scratch.

The drawback of thinking like a cook is that you simply have to trust that the chef’s recipe is the best way to make the dish since you haven’t made the time commitment to experiment with creating the recipe from scratch yourself.

The Cook and the Chef of Personal Finance

This cook vs. chef style of thinking can be applied to personal finance.

As a cook, you can choose to simply follow the financial advice given in personal finance blogs, books, and podcasts.

Or you can choose to be a chef and look at the raw math, historical data, laws, and regulations behind different investment techniques, asset allocation performances, and investment accounts.

Sadly, most people choose to be neither a cook nor a chef. Instead, they remain outside of the personal finance kitchen altogether and fail to learn about the basics of saving, investing, and building wealth. And by not learning the basics, they screw themselves over.

As I shared in a classic post titled You’re Screwed if You Don’t Understand Personal Finance:

Personal finance is a unique topic in the sense that you will get screwed if you don’t understand it.

This doesn’t hold true for most topics. Not understanding architecture, chemistry, engineering, or botany probably won’t hurt you.

You can merrily go through your day without understanding the algorithms underlying traffic lights, how your liver converts stored glycogen into glucose, how nuclear power grids function, or the intricate details of photosynthesis. Your ignorance in all of these topics won’t impact your quality of life.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t hold true for personal finance. Without understanding the basics, money will always slip through your fingers. You’ll have to keep spending life energy to accumulate more money; precious life energy that you could instead spend on traveling, spending time with family, and having more experiences.

For people who are completely ignorant about personal finance, the first step is to become a cook. Simply read what the chefs have written about saving and investing.

The next step, for those who are willing to make the commitment, is to become a chef. Look at the raw financial data and decide for yourself if a certain investment strategy makes sense.

So, today I put on my chef hat and tackle a topic that many in the personal finance community would consider heresy to even question: Is investing in a 401(k) actually a good idea?

A Short History of the 401(k)

401(k) plans were basically created by accident. In the 1970s, a group of high-earning individuals from Kodak approached Congress and requested that they be allowed to invest a part of their salary into the stock market and allow those investments to be exempt from income tax.

The IRS agreed to this and inserted section 401(k) into the existing tax regulations in 1978, which allowed individuals to invest part of their salary tax-free in the markets.

A few years later, an attorney named Ted Benna convinced his employer, The Jonhson Companies, to create a 401(k) plan for its employees, the first 401(k) plan ever created.

Then in 1981, the IRS issued new regulations that allowed employees to fund their 401(k) plans through payroll deductions. Soon after, the 401(k) plan became wildly popular and most companies began to offer plans to their employees as a way for them to save for retirement.

How a 401(k) Works

In a nutshell, a 401(k) is a plan offered by an employer to an employee that allows them to invest a portion of their income without being taxed on that income. Not all employers offer a 401(k) plan, but the ones that do allow you to select:

- Whether you want to invest in a Roth 401(k) or a Traditional 401(k)

- How much you would like to contribute from each paycheck

- What type of funds you’d like to invest in within your 401(k)

Roth 410(k) vs. Traditional 401(k)

There is one key difference between a Roth 401(k) and a Traditional 401(k).

Roth 401(k): You make your contributions after you pay tax on your income. Then, your investments grow tax-free and when you withdraw that money during retirement, you don’t have to pay taxes on those withdrawals. This means you receive no tax benefits now, but rather you receive them later once you begin to withdraw your money tax-free.

Traditional 401(k): You make your contributions before you pay tax on your income. Then, your investments grow tax-free but when you withdraw that money during retirement, those withdrawals will be taxed as ordinary income. This means you receive tax benefits now by reducing your taxable income, but you still have to pay taxes later once you begin to withdraw your money.

Note: Most companies offer a traditional 401(k) as the default option. Not all companies offer a Roth 401(k).

Selecting Your Contribution Amount

Once you’ve decided which type of 401(k) use, you then have to decide how much of your income you’d like to invest.

For 2018, the annual contribution limit for someone 50 or younger is $18,500. Those who are 50 or older are allowed to invest up to $24,500 per year as a way to catch up if they missed out on contributing when they were younger.

Once you’ve chosen how much to contribute, your contributions will automatically be deducted from each paycheck and invested in the funds you select in your 401(k) account.

Deciding What to Invest In

Once you’ve chosen which type of 401(k) to use and how much to contribute, the final step is to decide what to invest in.

This is an important distinction to make: A 401(k) is just an account you can invest in. You still have to choose what to invest in within your 401(k).

Many novice investors don’t realize this. I’ve had several conversations with coworkers in the past about 401(k)s and when I ask what they invest in within their account, they give me a funny look.

“What do you mean? I just invest some of each paycheck into my 401(k) account. Don’t we all invest in the same things?”

No, we don’t all invest in the same things. Your 401(k) is just the name of the account that holds your investments. What you decide to invest in – U.S. large cap stock index funds, International stock index funds, small cap stock index funds, bond index funds, money market funds, etc. – is completely up to you.

Fortunately, most companies have a “default” investment option that individuals can select when setting up their account. In most cases, the default option is something known as a “Target Date Fund”, which invests your contributions automatically in a mix of stock and bond index funds and adjusts this allocation over time based on which year you plan on retiring.

As you get older, the Target Date Fund automatically starts investing less of your contributions in stock index funds and more in bond index funds.

The expense ratios on these types of funds is typically around 0.7%, which is a bit high especially compared to something like the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund with an expense ratio of 0.04%.

However, for investors who have no clue what they’re doing, Target Date Funds offer a nice way to invest with as little hassle as possible. The fund company handles the investments, the rebalancing, and the asset allocation for you so you don’t even have to think about it.

But for the investor who wants to reduce the amount they pay in fees, they can take the reins into their own hands.

For example, when I started working for my current company last year, the annual contribution limit was $18,000 per year. For my age bracket, the Target Date Fund had an annual expense ratio of 1.01%. This means if I maxed out my contributions at $18,000 per year, I’d have to pay $181.80 in management fees no matter how well my investments performed.

Fortunately, I was able to defer the default Target Date Fund and instead chose to invest all of my contributions into an S&P 500 index fund with an expense ratio of just 0.04%.

I’m comfortable with this investment choice because I have a long investment horizon ahead of me and plenty of time to ride out the volatility that comes with investing in stocks. Also, Warren Buffett is a strong advocate of investing in the S&P 500, which makes me even more comfortable with this choice.

To quote Buffett’s investment advice that he gives to his heirs:

“My advice to the trustee couldn’t be more simple: Put 10% of the cash in short-term government bonds and 90% in a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund. (I suggest Vanguard’s.) I believe the trust’s long-term results from this policy will be superior to those attained by most investors — whether pension funds, institutions or individuals — who employ high-fee managers.”

I’m happy to invest in a fund that Warren Buffet so strongly believes in.

Should You Invest in a 401(k)?

Now that we know the history of the 401(k) and how it works, we only have one question to answer: Should you invest in a 401(k)?

To answer this, we need to address:

1. The benefits of investing in a 401(k) – employer match and tax benefits

2. The potential drawbacks of investing in a 401(k) – high fund fees and penalties on early withdrawals

The Benefits of Investing in a 401(k)

There are two clear benefits of investing in a 401(k): the employer match and the tax benefits.

Most companies offer an employer match, which means your employer will literally match your contributions you make to your 401(k) up to a certain percentage.

For example, suppose your employer matches the first 5% of your contributions and you make $40,000 per year. This means when you invest the first $2,000 into your 401(k), your employer will also contribute $2,000, which instantly doubles your balance to $4,000. This is free money that your employee is willing to give you, which is an unbeatable deal.

The second clear benefit of investing in a 401(k) is the tax benefit. To illustrate this, I’ll use myself as an example.

Last year I decided to invest $650 from each two-week paycheck into a 401(k) account. Here is what my paycheck looked like without contributing to my 401(k) account:

| My Paycheck Without Any 401(k) Contribution | |

| Gross Pay | $3,120 |

| Social Security | $193 |

| Medicare | $45 |

| Federal Tax | $477 |

| State Tax | $100 |

| Local Tax | $39 |

| 401(k) Contribution | $0 |

| Net Pay | $2,264 |

| Total Amount of Gross Pay I Kept | $2,264 (72.5% of gross pay) |

My total gross pay was $3,120, but after paying Social Security, Medicare, and all the different levels of federal, state, and local taxes, I was left with $2,264. I kept 72.5% of my total gross pay.

Now, here is what my paycheck looked like once I did start contributing to my 401(k) account:

| My Paycheck With a 401(k) Contribution | |

| Gross Pay | $3,120 |

| Social Security | $193 |

| Medicare | $45 |

| Federal Tax | $314 |

| State Tax | $74 |

| Local Tax | $39 |

| 401(k) Contribution | $650 |

| Net Pay | $1,802 |

| Total Amount of Gross Pay I Kept | $2,452 (78.5% of gross pay) |

By contributing $650 from my two-week paycheck to my 401(k) plan, I was able to significantly reduce my federal and state taxes and keep 78.5% of my total gross pay. None of the $650 I saved was taxed at all. It simply bypassed the tax man altogether and jumped safely into my S&P 500 fund in my 401(k).

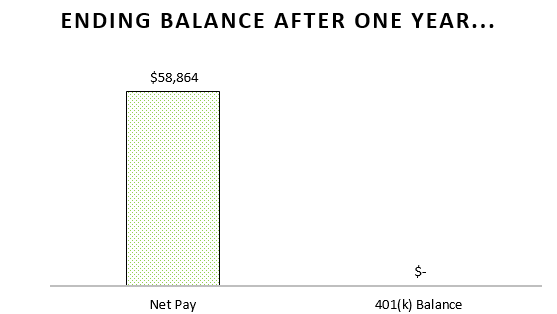

Let’s visualize the dramatic difference between contributing $650 each paycheck compared to not contributing at all.

Here is how much of my income I would retain after one year without contributing to my 401(k):

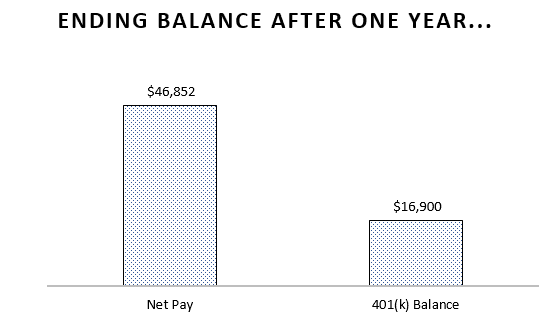

And here is how much of my income I would retain after one year with contributing to my 401(k):

I would retain a total of $63,752. That’s a difference of $4,888.

Keep in mind that these calculations don’t even include an employer match, which I wasn’t eligible to receive at the time since I hadn’t been with the company for long enough.

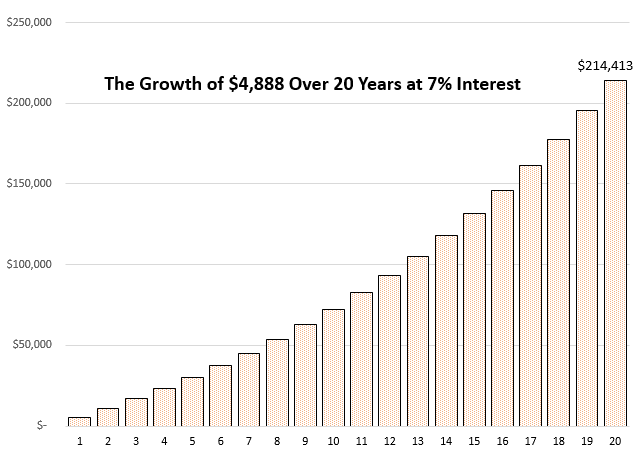

Maybe $4,888 doesn’t sound like much, but here’s what an extra $4,888 can become if it’s invested for 20 years at a 7% interest rate:

That’s over $214,000 in 20 years.

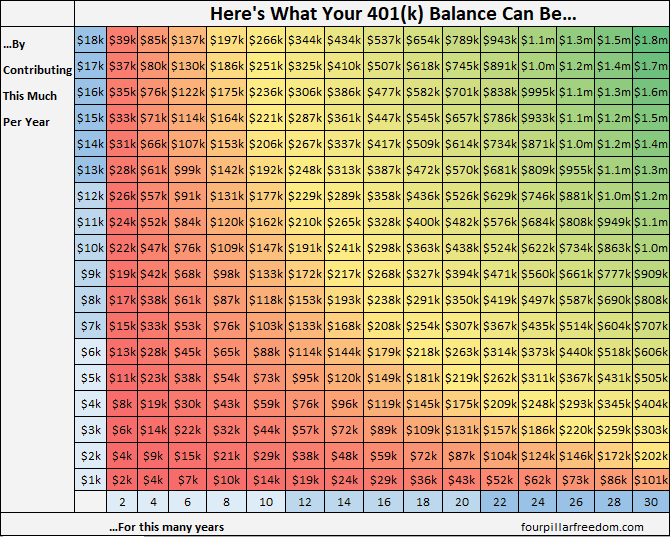

To see the true impact of contributing to a 401(k) over many years, check out the grid below that shows what your 401(k) balance can grow to based on your annual contributions and the number of years you contribute.

The grid assumes you start with a balance of $0 and earn 7% annual returns.

By contributing at least $18,000 per year, you can become a 401(k) millionaire in just 24 years, assuming a 7% annual growth rate on investments.

Related: Here’s How the S&P 500 Has Performed Since 1928

The Potential Drawbacks of Investing in a 401(k)

We’ve seen the amazing tax benefits and the powerful effect of an employer match that comes with a 401(k), but some people would argue that there are two potential drawbacks of investing in a 401(k):

1. High fund fees

2. Early withdrawal penalties

Let’s take a closer look at both of these issues and determine if they’re actually drawbacks that you should worry about.

High Fund Fees

As I shared in my example above, the default Target Date Fund in my 401(k) came with an expense ratio of over 1% annually. Fortunately I was able to find a low cost S&P 500 index fund alternative with only a 0.04% ratio, but not everyone is so lucky. It’s quite common to pay a 1% expense ratio in many 401(k) funds.

This begs the question: Is it better to invest in a taxable account in a fund that has a much lower expense ratio?

Fortunately, My Money Wizard has already run the numbers for this exact question.

From My Money Wizard:

Let’s compare someone paying a 1% expense ratio in a 401k versus someone who chooses to invest into the lowest fee, taxable index fund around – a Vanguard fund with a 0.05% expense ratio.

We’ll assume the market returns 7% over their 20 years at the company.

Retirement Rick invests in a 1% expense ratio 401k. Taxable Terry invests in a .05% expense ratio taxable Vanguard fund.

| Retirement Rick | Taxable Terry | |

| Salary | $ 70,000 | $ 70,000 |

| Contribution | $ 18,000 | $ 18,000 |

| Taxable Income | $ 52,000 | $ 70,000 |

| Taxes Owed | $ 7,196 | $ 11,696 |

| Extra to Invest | $ 4,500 | $ 0 |

| Total Invested Each Year | $ 22,500 | $ 18,000 |

| Account Balance after 20 years | $ 845,615 | $ 733,902 |

In the above example, because Retirement Rick contributed to a 401k, he reduced his taxable income by $18,000 per year. This reduced his tax bill, which left him an extra $4,500 in his pocket to invest outside of his 401k, every single year!

So while Taxable Terry could only invest $18,000 into a taxable Vanguard fund, Retirement Rick could invest $18,000 in his 401k, plus $4,500 into the same taxable Vanguard fund, for a total of $22,500 invested each year.

By the end of his 20-year career, Retirement Rick had $845,615:

- $662,140 in his 401k

- $183,475 in his taxable account

So, Retirement Rick would end up with $112,00 more even with the considerably higher fees.

This shows that the tax benefits of contributing to a 401(k) are often enough to outweigh any high fees you may have to pay on funds within your 401(k).

Early Withdrawal Penalties

The other big reason people may hesitate to invest in a 401(k) is because they can’t actually access that money until age 59.5 without paying a 10% penalty on their withdrawals.

As an alternative, many people choose to contribute to their 401(k) only up to the employer match and then invest the rest in IRAs or taxable accounts so that they have “access” to those investments if they need to withdraw them and use them to pay for anything.

However, many people have a fundamental misunderstanding of how this penalty actually works. In this post, Joel from FI 180 provides some clarity on the 401(k) early withdrawal penalty:

- You can withdraw your money before age 59½ if you pay an additional 10% income tax (the “penalty”)

- This tax only applies on the amount you withdraw, NOT the entire account balance.

- Penalty-free methods for early withdrawals do exist: these include Roth Conversion Ladders and Substantially Equal Periodic Payments (SEPP).

And in this analysis, Brandon from The Mad Fientist runs the numbers to show that maxing out 401(k) contributions and simply paying a penalty on early withdrawals is actually a better alternative than simply investing in a taxable account instead.

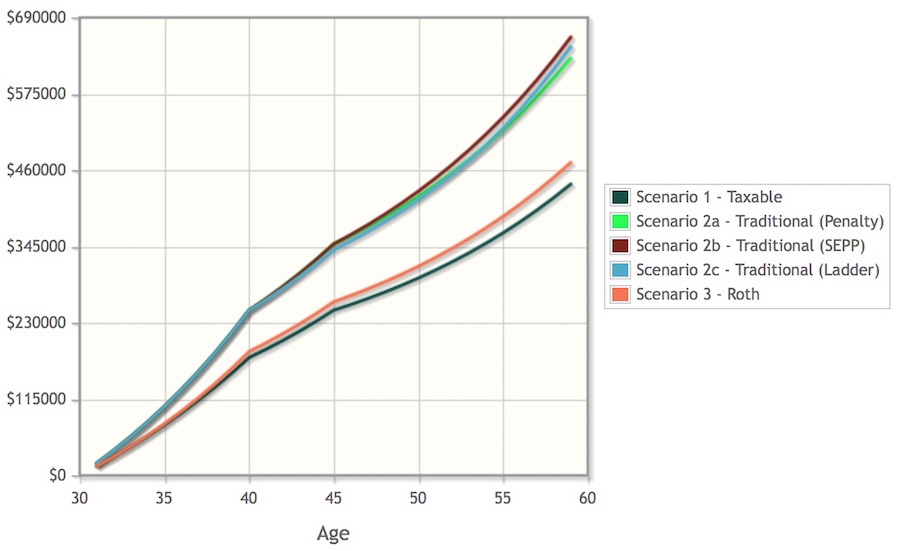

He uses the example of a 30-year-old woman who plans to retire at age 40. During her working years, she has $18,000 available to invest. Once she retires at age 40, she won’t need to withdraw money from investments until age 45, at which point she will need to withdraw $9,000 each year from age 45 to 60.

He runs the numbers on five different investment and withdrawal scenarios – investing in a Roth 401(k), a taxable account, or a Traditional 401(k) with withdrawal strategies including paying the penalty, using a Roth conversion ladder, or using a SEPP.

He finds that contributing the max to a 401(k) account during the woman’s working years and then paying a penalty to withdraw $9,000 each year from age 45 to 60 leaves her with about $100,000 more than if she had simply invested in a taxable account:

This is an incredible finding. It turns out that the tax benefit of maxing out 401(k) contributions offers a massive advantage over investing in a taxable account even if you have to pay the early withdrawal penalty.

Bryan from Smart Money Better Life echoes this point, saying:

If there are months or years where I don’t need the IRA income, it just keeps growing in my account, tax free. So it’s like a faucet I can turn on or off as needed.

On the other hand, after-tax income is ALWAYS taxed even if I don’t spend it. It’s ALWAYS taxed. Did you hear me? IRA income is ONLY taxed when I need it. This right here can be the difference (when you take into account compounding) of a HUGE SUM over 30 years.

And Joel from FI 180 drives this point home:

Think about it: every dollar you take home in your paycheck is ALWAYS taxed, regardless if you spend it or save it. Put this money into a 401(k), though, and we’re ONLY taxed at withdrawal time, on the specific amount we withdrew.

The rest of the money can keep on growing, tax-free. Add this to the fact that I should be in the lowest possible tax bracket in FIRE and you can see why this makes so much sense.

Conclusion

The tax benefits of contributing to a 401(k) along with the employer match make it a great investment account to utilize if you have access to one.

From running the numbers, we’ve also seen that the two arguments for not contributing to a 401(k) – high fund fees and early withdrawal penalties – are not supported by data.

It turns out that the tremendous tax benefits of contributing to a 401(k) are enough to offset high fund fees and early withdrawal penalties, which makes a 401(k) preferable to investing in a taxable account.

Keep in mind that if you’re able to max out your tax-advantaged accounts each year, then of course it’s okay to invest in taxable accounts with any leftover money.

So, after putting on my chef hat and running the numbers, the verdict is in: Yes, you should invest in a 401(k) if you have access to one, even if the fund fees are higher than those at Vanguard and even if you have to pay the early withdrawal penalty at some point in the future to access your money before age 59.5.

- The Ad Revenue Grid - August 6, 2021

- Attract Money by Creating Value for a Specific Audience - July 13, 2021

- The 5-Hour Workday - March 26, 2021

Full Disclosure: Nothing on this site should ever be considered to be advice, research or an invitation to buy or sell any securities, please see my Terms & Conditions page for a full disclaimer.

Good stuff here Zach..Thank you for the article. I hated the fees in my 403b and did not pay into it for the first 10 years. Once I learned this in the past 2 years I decided to max out both a 403b and 457 plan ( I am a teacher) and it is adding up quickly with almost $40,000 tax savings per year and that growth in the accounts. If I keep it up, once I am 50, I will put in an extra $12,000 for catch up and retire early at 55 while I take the penalty off of the balance I withdraw and be content. Thanks for sharing!

Hi Barry, I just wanted to point out something Zach didn’t mention in his post! There is another rule about accessing 401(k) money early that might help you out. I don’t know the in’s-and-out’s of it 100%, but it’s something like if you turn 55 and still work for the company that you have your 401k with, then I believe you can retire at any point during the year you turn 55 and access the money penalty-free. Check it out! It’s a little-known rule.

Also to Zach, thanks for the great article! I really enjoyed it. Also, it’s evident in your graphics, but you DO pay Social Security and Medicare tax even on pre-tax contributions. So it doesn’t completely slip by the tax man, but still better I reckon! I never realized it until I was creating an Excel spreadsheet for my paycheck breakdown one day haha.

Thank you for the comment! That does appear to be correct and since my wife and I are not trying to do anything too fast with regards to FIRE, this is incredibly helpful. I completely forgot about the rule myself.

Again, thanks!

Yes, Barry! My wife and I also both work in education and have recently started maxing both the 403(b) and 457. It’s an amazing amount going in pre-tax.

Thanks for the article, Zach. I’d done some quick runs to come to the same conclusion, but as always yours are meticulous and well illustrated. I always find your posts informative.

That’s awesome that you’re able to contribute to both a 403b and 457 plan. It sounds like those savings are starting to add up pretty quickly – kudos to you!

My employer does not contribute to our 401k’s. The choices of funds are not gaining very much but the fees are outrageous. Once I figured out that the fees were negating any gains, I decided that pulling out of the 401k was better than giving my money to the fund managers.